September 16, 1776

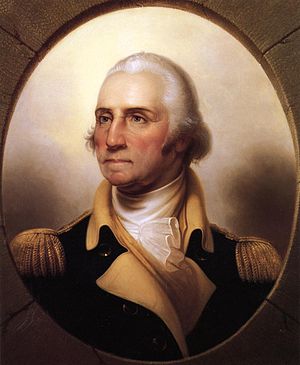

A cold faceless wind swoops up from the Vye and sweeps over the heights. George Washington, supreme commander of the Continental Army, tugs at the stiff facings, pulling the flaps tighter around his neck. Lifting his head, he turns in the saddle and gazes south – out over the flicker of countless campfires to a distant city’s gentle glow. As if scanning the empty waves and lonely horizon for signs of sail, his eyes roll to the east, stretching over the far reaches of Long Island. They drop to the subtle dip of swaying lights that cut through the thickening mist of warm waters touched by the cooling air. The filtered light rises up from the men-of-war anchored in the river. He sighs.

It is September 16th, 1776 on the eve of what will be called the Battle of Harlem Heights. The night falls heavily on an exhausted army. Two days of fight and flight have taken their toll; two days when an entire army fled before its enemy only to turn and lash out, claiming its first victory in a war that will last many years and prove to be one of attrition.

“Today we bloodied your nose,” Washington whispers staring out into the night. “That is all. Though all the more to make you eager for the final kill.”

He knows. The lights that scan the horizon are but beacons of despair to mark the presence of a supreme power, a power that casts the promise of continued violence upon these shores and upon the hopes and aspirations of a fledgling collection of merchants, mechanics and farmers peering out from behind earthen barricades. Each man stares into the dark, hoping his proven enemy will spend these next several days in repose, like a slumbering lion bloated from the day’s kill.

As he gazes into the darkness, he notes smaller dots of light moving slowly across the river from Newtown Bay.

“More troops to fill the coffers of what faces us,” Washington says in a low voice. “A nightmare brought to flesh. Perhaps General Howe is not quite the dilatory commander that my staff speaks of. There may be a surprise in store for us in the morn.” He sighs, knowing no matter how exhausted they are, he must confer with council.

He swings around eying his staff. ‘Though perhaps not now,’ he thinks. ‘We are all tired. So damned tired.’

Billy, Washington’s devoted slave, sits his horse near the General’s side. Just beyond sits Washington’s aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed on his horse at a respectful distance.

‘I cannot allow this day to be tarnished by concern for the future,’ Washington thinks, leaning back, one hand twisting the reins. ‘Not after the way these men performed. How gallant they stood in open field before the best Howe had. Not just stand, but they turned their enemy. Made them run. For that alone they proved their worth to those pigheaded bastards out there. If but it were enough for all the tomorrows putting an end to this.’

“But alas we have not the luxury,” Washington says, loud enough for all to hear. Reed nudges his horse closer.

“Sir?”

Washington chances him a quick glance. “Nothing Colonel. Nothing of concern,” he adds.

Without further word Washington tugs on his reins. He lifts his eyes to the stately manor further along the heights, its long pillars illuminated by the soft glow of a torch propped up by the porch. The Roger Morris mansion rests on the highest point of Harlem and is one of the finer homes on Manhattan Island. Knowing what awaits, he slaps the leather cords, hurrying his horse along the deserted post road nearby.

Inside the mansion, the hearth’s inviting fire licks the warming air. A long deep sigh fills the spacious room. Washington settles back heavily in a richly floral wing back settee with returning wing arms above loose cushion seats raised on carved and gilded legs. Nestled near the fire, he is dressed in small clothes. His hat and coat hang in the foyer closet with boots and spurs on a small wooden table next to the large grandfather clock that straddles the split level stairway. Head leaning back against the soft cushion, he closes his eyes, finding himself counting the long standing clock’s slow precise chimes.

‘Good God. Eleven o’clock,’ he thinks, opening his eyes. ‘And I haven’t even opened the day’s correspondence or written an account of battle.’ He rubs his eyes exhaling slowly. He knows it will be at least another two hours before he completes his report and receives final news of troop displacements. He moans. “And I must issue the final orders of the day so they may be disbursed among adjuncts before dawn.” He knows that then and only then may he lay his head to pillow.

“I once thought to go to sea,” he chuckles lightly to himself. He remembers his mother inquired the advice of a distant relative in London and his council was definitive. It must be avoided at all costs. Therefore it was.

Washington’s hand slips between the flaps of an inside pocket and he fingers his glasses.

His hand holds as he looks across the empty room. Living in a time when spectacles are considered humiliating and weak, as if one were to develop a club foot or hunched back, he is cautious no one is present before placing them on his nose.

‘I must call a war council,’ he thinks. ‘However, requiring one so early may be waste of time.’ He wipes the lens on a handkerchief while shaking his head. ‘It would be far better to while away the morning hours in bed allowing my staff a well deserved rest. My illustrious foe, resplendent in his laced regimentals, will but rise and gaze out at our entrenchments. He will then turn from the heights and accept a lavish breakfast. “Oh I am sure of it,” he said tapping one arm of the chair.

Washington sits trying to convince himself that his opponent dare not attack in the morning. ‘Howe did not press his advantage after our debacle at Jamaica Pass,’ he thinks. ‘Nor did he follow up with an attack as we desperately clung to Brooklyn Heights, hoping to escape annihilation. And the folly of waiting nearly three weeks after our rout on Long Island. He then lands at Kipps Bay instead of to our rear at Kings Bridge… incredible. And if I am to be swayed by such logic, he will not chance pressing his men up these slopes of Harlem Heights from where we clearly hold the vantage. He will hold his lines before mine seeking to outflank us.’

Yet the earlier sight of more troop transports flowing from Long Island continued to gnaw at his better judgment.

“Damn it,” Washington moans. “Incredulous as it may seem, Howe appears completely unhindered by any time constraints or pressure from his lordships in England. While I must deal with a vacillating Congress that readily sways with any wind of public dissent.”

Washington frowns, adjusting his glasses. He swings in his chair, glancing across the room to an oak joint stool. Often referred to as a coffin stool, it now serves nicely as a small side table. His frown deepens,as he notes the face of the stool lay vacant. Normally layered with parcels from the post, he looks forward to leafing through the day’s correspondence, looking for word from home, particularly from his brother, and news of the additions to Mount Vernon.

Footsteps echo through the foyer. Washington turns as Colonel Reed enters beneath the large arched entrance to the expansive sitting room.

Washington rips his glasses off. “Colonel,” he says wearily, his voice echoing the fatigue that grips every inch of his body. He waits, watching his aide-de-camp place his coat and gloves on the seat of a side chair just inside the room.

“Yes, your Excellency?” Reed asks, turning to face his commander.

“What say you?” Washington inquires. “Will our over-confident opponent test our mettle and attempt to resolve this present contest in the morn?”

“Your Excellency, if you mean will General Howe stage an attack on our entrenched position, then my answer is a resounding no. He lost his nerve standing among his troops on Breeds Hill watching them topple to the earth all around him. It has made such a devastating impression that he will not hurl his legions against what he now faces on the Heights.”

“Do you question his courage?” Washington asks evenly. Even though an enemy, a gentleman’s honor is one not dealt with so openly.

“The furthest thing from my mind,” Reed adds quickly. “He stood before his troops leading them up the side of that hill outside Boston. Only after most of his officers were dead or wounded and he was basically left standing alone did he march what was left back down. He quickly regrouped and called up reinforcements staging another try. It was a miracle he walked away from that battle unscathed.”

“No,” Reed asserts, “General Howe is a man of honor. It is not his courage that is in question. It is his stomach. He has none for a direct attack. I sincerely believe he fears the slaughter.”

Washington eyes the astute Philadelphia lawyer. “I agree,” he says, pushing further back in the comfortable chair.

“Your Excellency?” Reed asks, gesturing with an empty glass taken from a richly aged mahogany serving table. Several bottles of wines and sherry lay atop the plain molded top. Dovetailed construction with single full length drawer, the ring-turned reed legs taper to delicate ball feet, the table is one of the many imported French and English pieces left behind by Colonel Roger Morris. Fleeing to England at the start of the year, they did so just prior to General Lee’s expected arrival in New York. A staunch inimical, he and his wife Mary Philips had abandoned the newly-built Palladian style mansion.

Washington sits up. “Thank you Colonel, but no. Billy has already tried to entice me with a hot flannel. Though the nutmeg would be pleasing, I am afraid the beer and gin would hinder the business that demands my attention prior to retiring. But please… do not shadow my necessity… indulge. You most certainly deserve it.”

“Your Excellency is most kind and I thank him, but presently I require no spirits.” Reed, a man intensely cognizant of protocol, not to mention ambition, reluctantly lays the glass back down on the smooth surface.

Washington nods absently. He does not encourage familiarity with his staff. Seldom will he express humor in their presence, even with his closest aides. One of dry wit and curtailed mirth, he considers it a commander’s role to hold himself aloof, with a certain amount of grave sobriety. From such a position he is convinced power is maintained over both subordinates and civilians.

The same holds true of his attire. As an aide to the unfortunate General Braddock who lost his life and most of his troops outside Fort Duquesne during the last war, Washington paid close attention to the way the British officer maintained his rank. He became convinced a commander must convey character and leadership through appearance. Therefore he is never seen out of uniform, insisting his officers do likewise, all this to present a united front.

Using cloth imported from England, Washington wears a blue wool coat with buff wool rise and fall collar including buff cuffs, lapels and lining. A long row of yellow metal buttons, ten each, layer each lapel as well as several adorning each cuff. His small clothes, waistcoat and breeches, are of matching buff wool with gilt buttons. Riding boots and a fine white linen shirt complete his array.

“Still,” Washington says, mulling over Howe’s next possible move, “we must make preparations. It is best to err on the side of caution. Send word. I want a council of division commanders and all brigadiers present at headquarters prior to first light.”

“Yes your Excellency, I will send word.”

“Also bring me final troop displacements for this evening.”

“Very good sir.” Reed turns to leave.

“Oh, before you go,” Washington says, with a quick glance at the oak joint stool just to the right of the fireplace. “I note the post has not come this day.”

Reed follows his commander’s gaze to the small table left vacant of the usual pile of sealed parcels. A man of exact regularity, Washington is accustomed to settling in with personal correspondence prior to retiring to his office for official business.

“My apologies your Excellency. The post arrived not one hour ago. The satchel remains in my office. I will see to it immediately and return directly.”

With that, Reed is gone. Only the persistent clicking of the tall clock’s pendulum and Reed’s fading boots reverberating down the elongated hallway spoils the silence. The mansion is usually a blur of activity accommodating officers, their runners and the seemingly countless visitors. However the day’s fight appears to have taken the wind out of the army including the supreme commander’s personal staff. Those officers not overseeing sentries, sleeping in makeshift tents, or propped up in entrenchments lay asleep in some of the estate’s numerous rooms or out buildings.

Washington closes his eyes. His head abruptly snaps up in time to see Reed return from his errand.

If you want to Read More about Washington, Battle of Harlem Heights, or William Howe, we recommend the following books:

Check out the following articles on Revolutionary War Journal

Shades of Liberty is the exciting new action-packed series that chronicles African Americans who fought in the American Revolutionary War. Click above for a preview and link to Amazon Books and follow the adventures of Josiah, Book 1 of the Shades of Liberty Series. Josiah is a runaway slave and patriot soldier in Washington’s army. He faces death and discrimination from both a deadly enemy and soldiers in his own army. Josiah and fellow black patriots fight for America’s freedom, believing in a new nation that claims all men are created equal. They hope, they suffer, and many die striving for their rightful share of that promise – a promise disguised in many shades of liberty.