1775 – 1776

In February, 1775, the 40th Regiment of Foot was stationed in Dublin, Ireland. Because of developing hostilities in America, they were ordered to hold themselves in readiness. In accordance, they marched to Cork and on May 8, 1775, under the command of Major James Grant, departed the British Isles for Boston. The 40th was composed of eight companies. There were twenty seven officers and four hundred and forty rank and file. They arrived in Boston on June 25th, a week after the Battle of Bunker Hill, and put under the direct command of General Thomas Gage. In August, two additional companies were added to the regiment, as required that all regiments serving in America were to have ten companies. However, these two additional companies were to remain in England. It was in August of 1775 that chief command of British forces in America changed hands from Gage to Lieutenant General William Howe.

The 40th, along with the British army, wintered in Boston. Cut off from food and supplies from the mainland, they faced malnutrition and suffered from lack of heating fuel. When the Americans fortified the high grounds on Dorchester Heights, Gage ordered an evacuation of the city. The 40th boarded the Spry and Success as the rest of the British army, numbering 8,906 men, were transported to Halifax departing March 17th, 1776. At this time the 40th strength was reduced to 418 due to sickness.

Shortly after arriving in Nova Scotia, a detachment of 140 men under their commander, now Lt. Colonel James Grant, departed aboard two transports, under the protection of the frigate Scarborough. They were bound for Georgia where they hoped to obtain rice for the army. Note: Lt. Colonel James Grant, now heading the 40th , is not to be confused with Colonel James Grant who formerly commanded the 40th, but was promoted to Colonel and given the 55th regiment. Later he would be promoted to Major General and given a brigade. Arriving Georgia, they succeeded in making off with eighteen vessels of grain with the loss of one man killed, one wounded, and one missing. They arrived back at Halifax in April.

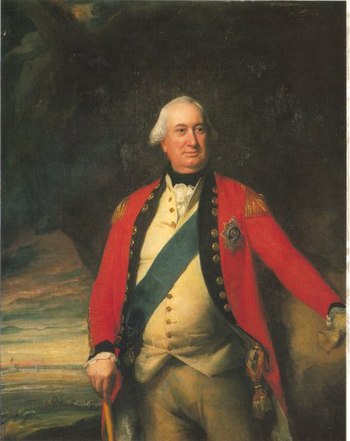

While in Halifax, General Howe decided to form two Battalions of Light Infantry and two of Grenadiers. Companies of Light Infantry and Grenadiers were taken from each regiment (the 40th included) to form these battalions. On June 10th, the army having rested and refurbished as well as restructured, departed Halifax for New York City. They arrived off Staten Island on July 2nd, 1776. Here the 40th was reinforced and formed in the 4th Brigade along with the 17th, 46th, and 55th, under the command of now Major General Grant (former colonel of the 55th). Note: Another Colonel Thomas Musgrave was commander of the 64th , and while in Halifax, was given command of the newly formed 1st Light Infantry Battalion. Some internet sites do not make this distinction and confuse the two.

Battle of Long Island

On August 22, 1776, the 40th , part of the 4th Brigade under the command of Major General James Grant, invaded Long Island. Before dawn on the morning of August 26th, the 40th, along with the rest of General Grant’s command, followed along the bay and attacked the American right wing then under the command of General Lord Stirling. Here Grant’s troops, along with ten cannon, kept their distance maintaining a constant fire with the Americans serving as a distraction (as the Hessians were doing along the center). This allowed Generals Howe and Clinton to flank the American far left and fall upon the ‘rebels’ from the rear. Grant’s forces then attacked in earnest along with the 2nd Battalion of Grenadiers and the 71st Regiment. Most of Lord Stirling’s command escaped across a nearby morass to the defenses at Brooklyn while he and several companies of Smallwood’s Marylanders sacrificed themselves to hold the attacking forces at bay.

During this action, Lt. Col. James Grant, commander of the 40th was killed. The Americans, upon hearing the news, thought it was Major General James Grant who had been killed. Of the 40th, one other rank and file was killed and five were wounded. Lt. Colonel Thomas Musgrave was given command of the 40th on August 28th, 1776.

The 40th did not take an active role in the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16th. They did not accompany Howe’s attempt, on October 12th, to get upon Washington’s rear by landing a considerable force along the coast of Westchester County. The 40th remained before the American defenses along Harlem Heights under the command of Lord Percy. On October 28th, Howe attacked the American forces dug in along White Plains on October 28th. Leary of what he considered strong defenses, he ordered only a small section of his army (the extreme left wing) to move forward. Though the British drove the ‘rebels’ extreme right in, most of Washington’s army remained behind their defenses. Howe still considered the American position to be very strong and waited for reinforcements before renewing the attack. The 40th arrived on October 30th with the rest of the 4th Brigade and two battalions of the 2nd Brigade.

The assault was to take place on the 31st, but a rain storm postponed it giving Washington the opportunity to shift his forces to higher ground at New Castle. Howe decided this offered Washington a better opportunity for defense and decided to turn his attention south to Fort Washington on Manhattan Island. General Grant marched the 4th Brigade to Valentine Hill on November 4th. Only the flank companies of the 40th took part in the assault on Fort Washington resulting in several killed and wounded. Note: The light infantry and the grenadier companies of a regiment were called flank companies and considered the best in the regiment. The other companies were called battalion companies.

On November 18th, General Cornwallis crossed the Hudson above Fort Lee on the New Jersey side. The Americans retreated before his force. General Grant’s 4th Brigade, with the 40th, joined Cornwallis on November 24th. The pursuit of the Americans across New Jersey was carried on for three weeks until the Americans crossed the Delaware into Pennsylvania. Because the weather had turned severely cold, Cornwallis gave up the pursuit and turned out the army to winter quarters. The 40th, along with the 17th and 55th regiments settled in Brunswick.

1777

Battle of Princeton: After Washington’s victory at Trenton, General Cornwallis rushed his forces across New Jersey. While passing through Princeton on January 2nd , he left the 17th, 55th, and 40th before proceeding on to Trenton. They were put under the overall command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood. Arriving Trenton, he spent the evening cannonading and exchanging shots with the entrenched American Forces. He expected to renew the assault the next morning only to discover Washington had left during the night. The American commander decided to make a bold attack against Brunswick and the British munitions stored there. His path would lead his army through Princeton.

Lt. Colonel Mahwood had already received orders to leave that morning of January 3rd, for Maidenhead, a small villa about halfway to Trenton. With the 17th leading, he no longer made the road than he ran into the vanguard of Washington’s army commanded by General Mercer. Mahwood immediately swung the 17th into line of battle and attacked, driving the Americans back; General Mercer fell with multiple bayonet wounds, dying some days later. Washington came on the scene and rallied his troops who charged fiercely. The 17th , far out in front were unsupported by the 55th and the 40th who were also viciously attacked. The 17th made a desperate charge and forced their way through, eventually retreating to Maidenhead. The 40th soon found themselves embroiled in what became known as the Battle of Princeton. Fighting desperately, they could not reach Maidenhood and retreated back towards Brunswick. Knowing Cornwallis would be fresh on his heels and his men exhausted from the past three month’s exertions, Washington decided not to press the attack against Brunswick and retired toward Morristown for winter quarters. The 40th losses in this action was considerable.

The rest of the winter and spring of 1777 were harsh on the 40th. They were on constant garrison and picket duty with numerous skirmishes with the enemy. Their headquarters was in Amboy with the flank companies stationed in Brunswick. Howe tried to induce Washington from his strong defense on the heights around Morristown, but after repeated attempts, he decided to change the ‘seat of war.’ In June, 36 battalions embarked and sailed for Philadelphia. Lord Howe’s fleet could not make their way up the Delaware so the fleet instead sailed for the Chesapeake, anchoring on August 24th at Head of Elk in Maryland. By September 3rd, the army was rested well enough after their long voyage and marched towards Philadelphia.

Battle of Brandywine Creek

At first, Washington had delayed marching south when he learned of Howe’s departure from New York. When it was finally confirmed that Howe had landed in Maryland, he marched his army with all haste to block his path to Philadelphia. Because of Howe’s delay in preparing his troops, Washington was able to position his forces at Brandywine Creek, south of Philadelphia in Maryland. Howe advanced and attacked on September 11th, 1777.

For this engagement, the 40th were back in Major General Grants Brigade, along with the 5th, 10th, 27th, and 55th regiments. However the flank companies were with General Howe’s main column. The 40th saw little action receiving but one wounded man. Consequently the flank companies were heavily engaged and sustained several losses.

A provincial regiment of New York loyalists, called the Queen’s Rangers, were involved in a major action for the first time. They were formerly commanded by the infamous Rogers of Rogers Rangers who gained renown in the French and Indian War. However, Rogers became a drunkard and command was taken from him. At the Battle of Brandywine, the Rangers performed well under the command of Captain Wemyss of the 40th. Wounded at the battle was Captain John Graves Simcoe, captain of a company in the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers. He would be promoted to Lt. Colonel and given command of the Queen’s Rangers, leading them to fame in future encounters in the south. He would be given the command of the Queen’s Ranges, but not accept his command until mid-October, after the Battle of Germantown.

Battle or Massacre of Paoli

General Howe pursued the American Army north towards Philadelphia. On the 20th, Howe received intelligence that his army was being shadowed by a corp of Americans, fifteen hundred strong and commanded by General Anthony Wayne. He further learned that they were only three miles distant from his camp. He ordered Major General Grey with the 2nd Battalion Light Infantry, to which the 40th Light Infantry was now attached, and the 42nd and 44th Regiments to make a night attack against the American camp.

They drove in the American pickets and attacked the camp using bayonets only. They killed fifty three and wounded over a hundred more, capturing over seventy. Of the 40th Light Infantry, Captain Wolfe, along with three rank and file, were killed and four others wounded. This became known as the Paoli Massacre. During the upcoming Battle of Germantown, Wayne’s Pennsylvanian troops would enact revenge when they came upon the 2nd Light Infantry as pickets.

Battle of Germantown

This battle would shed fame upon the 40th and laurels upon its commander, Colonel Thomas Musgrave. On September 25th, General Howe encamped his army at Germantown, six miles north of Philadelphia along the Schuylkill River. The next day he lead two detachments of Grenadiers and a regiment of Hessian grenadies into Philadelphia. Washington got news in early October that Howe had further weakened his army by dispatching two regiments south to receive supplies from the fleet. Additional men were sent to Billingspoint Port, NJ, to quell militia activity. Washington saw an opportunity to attack Howe’s now eight thousand troops with his superior eleven thousand.

Howe posted his army along two roads that ran west to east and through the center of town. He positioned the 40th in an advanced post one mile to north of center at the Clivedon Estate , owned by Supreme Court Judge Benjamin Chew; otherwise known as the Chew House.

Another half mile further north, the 2nd Light Infantry was posted as pickets – the 40th light infantry company was part of this battalion. These two units were to receive the first blow of Washington’s army as General Sullivan and General Wayne’s divisions moved south along the road and attacked. Sullivan drove in the light infantry after stiff fighting. Colonel Thomas Musgrave moved his regiment up in line of battle and held Sullivan’s men in check. General’s Wayne’s men came on with a vengeance; fuming over their fallen comrades and eager to exact revenge. They drove Musgrave’s men back. In the fog and confusion of smoke, Musgrave was able to send the rest of his men along with the light infantry south while he took six small companies, about 120 men, and barricaded themselves inside the stone Chew House.

Sullivan and Wayne passed by the house and pressed their attack against the main British line. However, Washington came up with Lord Stirling and his reserve. Upon General Knox’s insistence, Stirling’s men laid siege to the house. Musgrave’s troops doggedly sustained cannon shot and musketry for nearly an hour, returning shot and afflicting numerous casualties on the American troops. Eventually, other battalions from the American left heard the firing and attacked the house instead of driving south against the British line. Musgrave held out until the American’s, low on ammunition and fatigued, retreated. General Grey and General Agnew’s third and fourth brigades pursued the Americans and rescued Musgrave’s besieged men.

On October 10th, Howe moved his army from Germantown towards Philadelphia. The 40th went into camp and wintered near the city while Washington moved his army to Valley Forge.

1778

Affairs took place at the beginning of 1778 that would have a direct impact on the 40th. France declared war on England and became American allies. Because of France’s strong navy and possible addition of their troops to the American cause, England decided to concentrate their forces along the coast. General Henry Clinton, now commander of all British forces in America made preparations that summer to evacuate Philadelphia and move his army to New York City.

Battle of Monmouth

Clinton left Philadelphia on June 10th and gradually made his way across New Jersey towards Sandy Hook, NY, arriving Monmouth on June 27th. The next day, June 28th, the army was put in motion. The 40th were in the lead under Hessian General Knyphausen with the responsibility of guarding the baggage. Clinton brought up the rear with the second division in which the 40th flank companies were involved. The vanguard of Americans, under General Lee, made first contact with the British. He soon became convinced that with the numbers of men under his command, he could not succeed and ordered a retreat. When Washington came up, he ordered a reversal and attacked Clinton. The battle raged all day with basically a stale-mate, however the Americans were left with the field of battle. The 40th flank companies sustained heavy casualties. During the battle, the 40th battalion companies, serving as pickets to guard the baggage, were attacked by an American light infantry. With the help of the 17th Dragoons, they drove off the Americans.

Early in the winter, Clinton decided he had adequate forces to fend off any attack from the Americans. He could afford to send an expedition to the West Indies to protect British possessions and annoy the French. He assembled five thousand troops under Major General Grant which included the 40th. They departed Staten Island in November and arrived at Barbados on December 10th, 1778. Here the 40th were involved in several actions against the French over the next two years.

1781

The 40th remained in the West Indies until June of 1781. Their ranks had been seriously depleted by disease when they returned to their old quarters at Staten Island. Soon after, Clinton organized a small expedition under American turncoat General Benedict Arnold to destroy privateers and collect Naval stores at New London, Connecticut. The 40th, now commanded by Major William Montgomery, sailed with the expedition on September 4th and passed through the sound arriving Groton, Conn. on the 6th. The troops were divided into two segments. One, commanded by Arnold, was to capture Fort Trumbull on the New London side of the harbor and gain possession of the town. The other, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Eyre which consisted of the 40th, 54th, some artillery, and some loyalist volunteer from New Jersey were to attack Fort Griswold on the Groton side. Fort Trumbull was abandoned. Fort Griswold was another matter.

Battle of Fort Griswold

Arnold had thought the Fort incomplete, but upon learning that was not the case and that it was strongly defended, sent word to Eyre to cancel the attack. However, the message arrived too late. The 40th and the 54th formed in two columns. They assembled on a small knoll called Avery’s Hill. Here they were to be joined by the New Jersey volunteers who were bringing the cannon through a swampy area. Not waiting for the cannon, they began the attack. Three columns attacked simultaneously against the doggedly held fort. Lt. Colonel Eyre was seriously wounded and the command was turned over to Major Montgomery who commanded the 40th. As the walls of the fort were breached, Montgomery was killed by a boat spike manned by Colonel Ledyard’s black slave Jordon Freeman. It was thrust into Montgomery as he cleared the north-east bastion. Command of the assault was turned over to Major Stephen Bromfield of the 40th. As the British swarmed into the fort, its commander, Colonel Ledyard offered surrender. Many of the British soldiers continued to fire upon the Americans as they tried to surrender, killing and wounding many. It was reported by eyewitnesses that Colonel Ledyard offered his sword to Major Bromfield. The officer accepted it then immediately thrust it thought Ledyard, killing him instantly. Eighty five Americans were killed, most of them after having surrendered. Sixty were wounded and seventy made prisoner. Forty eight British were killed and 150 wounded, in the assault, 25% of the attacking British force. Montgomery was buried in the fort’s parade ground prior to the British departing. General Clinton commended Arnold on the raid’s success, but chastised him on the high number of casualties. Major Bromfield was given command of the 40th on September 7th, 1781.

1782 – 1783

Fort Griswold was to be the last action the 40th saw in America. After Connecticut, the regiment sailed back to Flag Staff, Staten Island and their old camp. Here they remained throughout peace negotiations. Negotiations settled the war with peace being declared on April 15th, 1783. The 40th remained on Staten Island until August then moved to Laurel Hill on Manhattan. There they remained until New York City was nearly abandoned by British forces. The 40th was one of the last units to set sail on November 25th, 1783.

If you would like to read more about the British & Continental Armies, check out these free previews of Great books on Amazon

Click Here to Preview: Fusiliers: The Saga of a British Redcoat Regiment in the American Revolution

Shades of Liberty is the exciting new action-packed series that chronicles African Americans who fought in the American Revolution.

Also of similar interest on Revolutionary War Journal

Sources

Bancroft, George. History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent Vol. 9. 1875: Little Brown and Company, Boston, MA.

Copp, John J. Battle of Groton Heights, The Massacre of Fort Griswold. 1879: The Groton Heights Centennial Committee, Groton, Connecticut.

Ford, Worthington Chauncey. British Officers Serving in American, 1774 – 1783. 1897: Brooklyn Historical Printing Club, Brooklyn, NY.

Lambdin, Alfred. The Battle of Germantown. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 1877: Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 368 – 403.

Smythies, Captain R. H. Raymond. Historical Records of the 40th Regiment… from the Formation in 1717 to 1893. 1894: A. H. Swiss, Davenport, UK.

Trevelyan, Sir G. O. The American Revolution Vol. 4. 1922: Longman’s Green & Company, New York, NY.

Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution. 2011: Skyhorse Publishing, New York, NY